History of the Espresso Machine

The coffee cultures of Europe, Italy in particular, and the artisanally crafted latte and cappuccino cups of the U.S. owe a debt to one key building block – the espresso. Forged by a process of forcing highly pressurized water through a tightly tamped down portafilter of finely ground particles, the espresso’s history in commercial and home consumption has been inextricably tied to the technological advancements that made it possible.

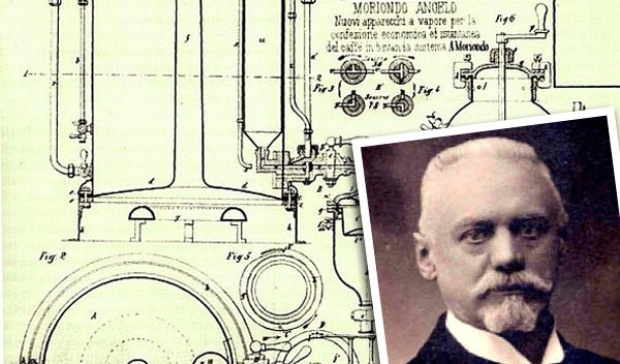

Espressos as a drink are a relatively newer invention, coming into existence at about 1884 in Italy. In this year Angelo Moriondo patented a steam-driven “instantaneous” drink-making device, thought to be the first of its kind anywhere. Unlike the modern espresso making machines and culture it would inspire, this initial creation brewed the drink in bulk.

Angelo Moriondo

By the turn of the century factory owner Luigi Bezzera had grown annoyed with the popularity of espresso, believing his workers were taking too long of breaks. As a way of fixing this he created some improvements on Moriondo’s design, patenting several in 1901, most of which centered around improvements aimed at creating single servings more rapidly.

Bezzera then sold his patents in 1905 to the La Pavoni company. It was La Pavoni that really brought espresso machines to the masses. When they started factory production of the machines in Milan that year the assembly line was churning out a whole machine once a day. Despite this seemingly slow paced output, it was enough to get the espresso craze underway in Italy.

As the nation urbanized and more young people were looking for meeting places in city centers, a culture popped up around espresso bars. With the government controlling the price of the drink, if it was consumed while standing up at a bar, these bars became the meeting places and social hubs of growing communities.

These initial espresso machines being steam driven meant the shots they created were different from what consumers are used to getting in coffee shops today. Steam driven espresso machines force the water through the grounds once enough steam pressure has built up. The pressure generated by these machines, however, isn’t as high as what can be produced by pump-driven ones and subsequently the crema can be much weaker or even just not present at all. One advantage of the steam driven machines is that less moving parts makes them cheaper to build and more durable so the technology is still seen in some less expensive at home machines today.

The next leap forward with espresso machines took places after World War II with café owner Achille Gaggia’s spring and piston enhanced steam process. With this machine, water was heated in a much smaller boiler, moved into a chamber for further pressurizing, and then “pulled” through to produce the espresso shot when the barista pulled the lever. This machine was capable of pressurizing the water nearly five times the amount that the purely steam method could and was the first that resulted in crema up to today’s standards.

Achille Gaggia

View our recommendations for the best coffees for espresso machinesIt was around this time that espresso began gaining popularity around the world. The 1950’s saw espresso bars become popular in throughout Britain and the major cities of the Americas. With the integration of steam wands (the part that froths the milk) new styles of espresso based drinks became easier to make. The British, with a history of liking their tea with milk, began drinking cappuccinos and with that a popularization of long drinks was born. It’s thought that lattes were first produced in the 1950’s as well in a Berkley Cafe owned by an Italian American wanting a larger form of cappuccino. The drink remained fairly regional until popularized by Starbucks in the 1980’s and 90’s who would also introduce the idea of flavored versions of the drink.

In the latter part of the 20th century, and into the 21st, further incremental improvements were made to the espresso machine. Introduced by Faema in 1961, the pump-driven machine is now commonly seen throughout the world. It automates the water-pressurizing process and can also accept water directly from a line rather than a tank that needs periodic refilling. Though improvements have been made, the core elements of commercial grade and prosumer espresso machines can be found in the Faema E61.

View our recommendations for the best coffees for AeroPressAnother addition to the espresso brewing landscape, one aimed at in-home use, has been air-pump driven devices. The most popular of these is the AeroPress, invented by Alan Adler in 2005. It’s essentially a plastic cylinder with grounds placed over a filter at the bottom, hot water poured over top and then the pressure to form the shot is created by inserting a rubber plunger that forms a seal and forces the water through the grounds.

As espresso machines improved their capacity for pressure and consistency, some also added automation features. While early machines were manual, requiring the barista to pump a handle to build pressure and pull the shots, machines improved their automation capabilities in stages referred to as semi-automatic, automatic, and super-automatic.

Semi-automatic machines would self pressurize to a preset pressure and then the barista would initiate the brewing of the shot with the pull of a lever and cut it off once enough water had been forced through. Automatic machines would self-pressurize as well, but they also used a fixed amount of water so the barista wouldn’t have to end the brewing. Super-automatics, sometimes seen in quick-service convenience type places or in vending machines, do it all. They grind the beans, tamp them down, pressurize the water and control the entire brew process – no barista required. Most coffee shops prefer manual or semi-automated machines since it allows the barista more control over brew time and shot quality.

From straight espresso shots to the most customized of latte orders, modern coffee culture throughoutthe world can be traced back to Italy at the turn of the last century. What started as a couple Italian businessmen wanting to boost productivity of their workers has evolved into a worldwide phenomenon.